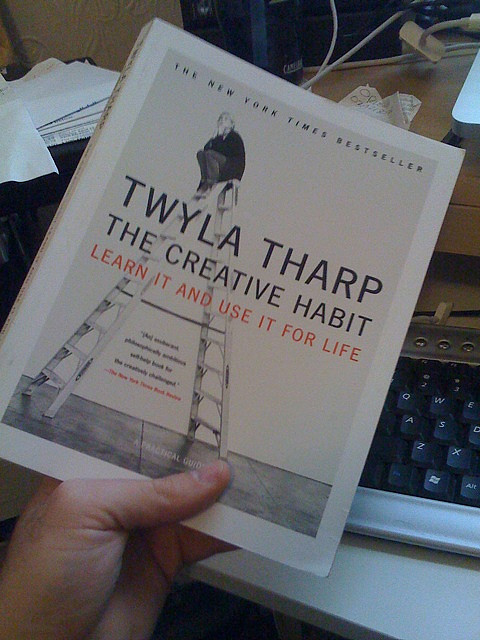

Twyla Tharp’s book, The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life (paid link) has been on the must read list for several creative people I admire. I finally got around to reading this book myself and now understand why it’s so influential.

Twyla Tharp is one of America’s greatest dance choreographers, with more than 130 dances produced by her own company, as well as The Joffrey Ballet, the New York City Ballet, Paris Opera Ballet, London’s Royal Ballet, and American Ballet Theatre. She’s been working in the creative realm since 1965, so it’s not surprising that she has learned a few things along the way.

Here are 10 of the lessons that impacted me the most from her book.

1. Begin your creative practice with a ritual.

Tharp starts her day by taking a cab to the gym. She says that having a ritual makes it a habit and getting in the cab is the first very important step. She needs to be warmed up (literally) to get creative and her time at the gym does just that.

This morning, in an email from Heron Dance, I learned about author Toni Morrison’s ritual.

“I always get up and make a cup of coffee while it is still dark — it must be dark — and then I drink the coffee and watch the light come. Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they expect to make the contact, where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process. For me, light is the signal in the transition. It’s not being in the light, it’s being there before it arrives. It enables me, in some sense.”

For me, not a morning person, I need to sit with my coffee, read a little news, and check my email. Then, I can turn off email and social media and work on my creative project for the day. The ritual can be as simple as lighting a candle or putting on music. Whatever the ritual, it’s a symbol that it’s time to do your creative work.

2. Be aware of what distracts you and give it up for awhile.

Being aware of what distracts you is oh so important. Distractions can seem quite reasonable.

“I’ll just check this email; there might be something important. I need to get the laundry started or there will be no clothes to wear tomorrow. I need to visit my grandmother right this minute, because my guilt is preventing me from doing my best work.”

If you get your important creative work done first, there is usually plenty of time to do the rest. Decide what’s most important and set realistic deadlines for getting it done.

Tharp suggests eliminating a persistent distraction from your life – temporarily at least, and see how your work is affected. For example, give up TV or movies or background music, whatever may be your biggest distraction, for a week. How does it affect the quantity and quality of your work?

For me, the Internet can be a distraction, particularly email and social media. I like the idea of working in 90 minutes bursts, with everything else (even phone) shut down for those 90 minutes. It’s amazing how much gets done.

3. Know what feeds your creativity.

It might be a tool. If you’re a writer, it could be a pencil and notepad. If you’re a painter, a sketchpad. For me, my tool is my camera. Whatever it is, you need to take it with you wherever you go. Ideas can come from anywhere at any time, and this way you’ll be ready.

It might be a practice. Perhaps you get your best ideas from a daily walk or from solitude or from reading. It might be doing physical work or mundane chores. Know what works for you.

4. Invest in yourself.

This is something I am slowly getting better at. A company needs investment to make money. People need investment to make the most of their creativity.

I know many artists who feel that they can’t invest in themselves until they achieve a certain amount of financial success. However, businesses don’t work that way. The investment sometimes has to come first and at various times along the way.

Tharp reminds us that money is a tool. Once you have your basic needs taken care of, the rest is up to you – to invest in yourself and/or others. Whether you put money into supplies or take the time for a class or workshop, the payoff is usually greater than the expense.

5. Scratch for ideas.

We often think that to be creative you have to come up with something brand new, out of thin air; something never seen before. Yet, really creativity is about finding new ways of combining or connecting what has been done before. Tharp says,

“Creativity is more about taking the facts, fictions, and feelings we store away and finding new ways to connect them.”

Scratching for ideas can seem like you are appropriating someone else’s work (which of course you should not do), but there’s a subtle difference. Others’ ideas can serve as inspiration for your own. For example, when I was at a workshop on neuroscience and meditation, the presenter, Dr. Dan Siegel, said the phrase “awareness is everything.” This was the impetus for a photography project around words and images that were the foundation of everything.

Tharp cites Harvard psychologist Stephen Kosslyn, in presenting four ways to act on an idea – generate it (from memory or experience), retain it, inspect it, and finally transform it. She suggests many ways of scratching for ideas, including reading, conversation, art, mentors, and nature.

6. Develop a spine.

While courage is important in creativity, the spine is the original thought or basis for your creative project. When you start to get off track, go back to the spine to help you stay on course.

The spine might not be apparent to someone experiencing the final product. For example, one of Tharp’s dances, Surfer at the River Styx, was originally based upon the Greek tragedy, The Bacchae. With only six dancers, she couldn’t recreate the whole story, so she took the main theme – pride and arrogance – and developed a dance around that theme. No one would know that it was based on this particular Greek tragedy, but she kept it in mind throughout the process.

For Tharp, the spine is a tool. It’s not the message, but it keeps her on message. She suggests finding the spine of your creative work with the help of a friend or co-worker, through music, or by remembering your original intentions and clarifying your goals.

7. Prepare to be lucky.

I love this one. As a perpetual planner, I have to realize that at some point, you just have to go for it. Live with uncertainty and see what happens. Recognize that your creative projects are not entirely your own. They need contact with the world to help them evolve.

I tried to do this with my current online photography workshop. While I planned out the weekly lessons in advance, I didn’t plan the extra encouraging emails for the rest of each week. I gathered some ideas, but waited to see what was happening with the participants and then responded to what they needed. I also wanted to do the workshop right along with them, and be able to share my firsthand experience.

Tharp also advises that part of preparation to be lucky is to be generous. It’s that whole karma thing. She says, “Generosity is luck going in the opposite direction; away from you.”

8. Know when you’re in a rut and know how to get out of it.

To Tharp, a rut is different from a creative block. It’s more like a false start. You know something’s not working, whether you want to admit it or not. This could be the result of a bad original idea, or bad luck, or sticking to past methods when new ones are required.

To deal with a rut, the first step is to admit you’re in one. Often, we spin our wheels or let pessimism creep in. These are signals that we’re in a rut. Tharp suggests brainstorming as a way to come up with a new idea and get past old habits. Also, challenge your initial assumptions and then act on those challenges. She warns against over working and over tinkering. Know when to stop for the day, and always leave something on the table for the next day.

9. Build your validation squad.

Every creative project needs constructive criticism along the way. Tharp suggests building your own squad of people to give you this important feedback. These people should be friends or people we admire. They are not competing with you and can be trusted to give honest feedback. We have to know how our work will connect with others and this can’t be done in a vacuum.

10. Just do it. It takes a long time and hard work to become a master at what you do.

There is no substitution for doing the work. Tharp presents a graph showing Mozart’s output over a 35 year period. It is similar to the work of many other masters in that output starts off slow (in the learning stages), hits full stride in the middle of their careers, and tails off a little as they age.

Devotion, commitment, and persistence are the essential qualities for a long and fruitful creative career.

“When creativity has become your habit: when you’ve learned to manage time, resources, expectations, and the demands of others; when you understand the value and place of validation, continuity, and purity of purpose – then you’re on the way to an artist’s ultimate goal: the achievement of mastery.” ~ Twyla Tharp

These 10 lessons just scratch the surface of this book. There are many others, as well as examples and exercises to illustrate her points. Check out this discussion group on Flickr about the book.

Which creative habit do you need to focus on most?

Image: By ario on Flickr (Creative Commons)

Thanks you for this post. Very useful and a good insight. It is a good idea to read multiple books on the one subject because they give so many different perspectives. This one certainly has its gems. Thanks for sharing.

Liz

Yes, it’s good to read what works for others and see what resonates with you. Everyone develops their own unique creative habits. Thanks for commenting, Liz.

Ten very good points – thank you for sharing them. My problem is I have too many projects and potential ones on the go in my head or partly started. This is food for thought and a couple of things, I regret to say, I don’t do as a rule.If I can follow this good advice maybe I will be able to focus better!

Ah, too many projects and ideas is also a good problem to have. I’d say pick the one that really makes you sing and start with that.

(1. Begin your creative practice with a ritual.) In a book I read about working at home, the author suggested that in order to separate home from work it is useful to find a ritual or habit…something as simple as donning shoes instead of slippers. It works for me.

Very good suggestion. Thanks, Geraldine.

Love the article, Kim! I’m also reading Twyla Tharp’s book in a class studying creative thought in advertising. I’m on chapter five, where Tharp introduces the box concept. I’m excited to learn what other inspiring life lessons the book holds. I’d love it if you checked out my blog post: http://lgrady.com/box/. Thanks!

I too loved this article Kim . Each point you touched on I can relate too. All of them ! Its a book I m not sure I could put down. Thanks for writing this and sharing. Perfect for me at this time. Lovely image you selected as well and nice work of that artist.