The Woods

The Great Work of Thomas Berry

One of the wisest writers I’ve ever encountered is Thomas Berry, Passionist priest, and historian of world religions and earth processes. Years ago, I read something that he wrote that has stayed with me ever since. That is, “The Earth is primary. Humans are derivative.” What do you think when you hear this statement? I’ve asked a few people recently if they believed this to be true and each one said yes. I then asked them if they thought that we, as a culture, live as if it were true and they all said no. For the past 100 years or so, humans have dominated the planet in a way that is extremely destructive. And, we’re all entrenched in this way of life. What’s a person to do?

Berry says that the great work of our time is to come to a new awareness of earth’s processes such that we live in a way that is mutually enhancing. We need an eco-awakening. Only then, will we take responsibility, not only for ourselves and our families, but for the entire earth community. By eco-awakening, I mean the realization that we are one part of an interdependent ecosystem. Another Thomas Berry quote which has always stayed with me is, ”The earth is not a collection of objects, but a communion of subjects.” Our world operates as a web of relationships and interactions, of which we are a part.

In a perfect world, eco-awakening happens quite naturally in childhood. Bill Plotkin says in his book, Nature and the Human Soul, that there are two stages in childhood that are essential to eco-awakening. If we’re deficient in either one (and most of us are at varying levels), we can still develop them at any time. The purpose of this post is to get you thinking of your early experiences and where you might be deficient. Below I’ll share my early experiences and how I work on them now.

The Preservation of Innocence (early childhood)

“The nature-oriented task of early childhood is the preservation of innocence, the capacity for present-centeredness. To be fully present to the here and now is essential to human development, especially when it comes to relationality and to the skills of empathy and compassion. After early childhood, the cultivation of present-centeredness is accomplished through a person’s own efforts rather than their parents’ (or others’). In addition to mindfulness practice, present-centeredness can be cultivated through regular periods of attentive solitude in wild or semi-wild places, devoted play with any of the expressive arts, psychotherapies that emphasize present-centeredness, the practice of presence and innocence in social settings, and, last but not least, apprenticing to infants.” ~ Bill Plotkin

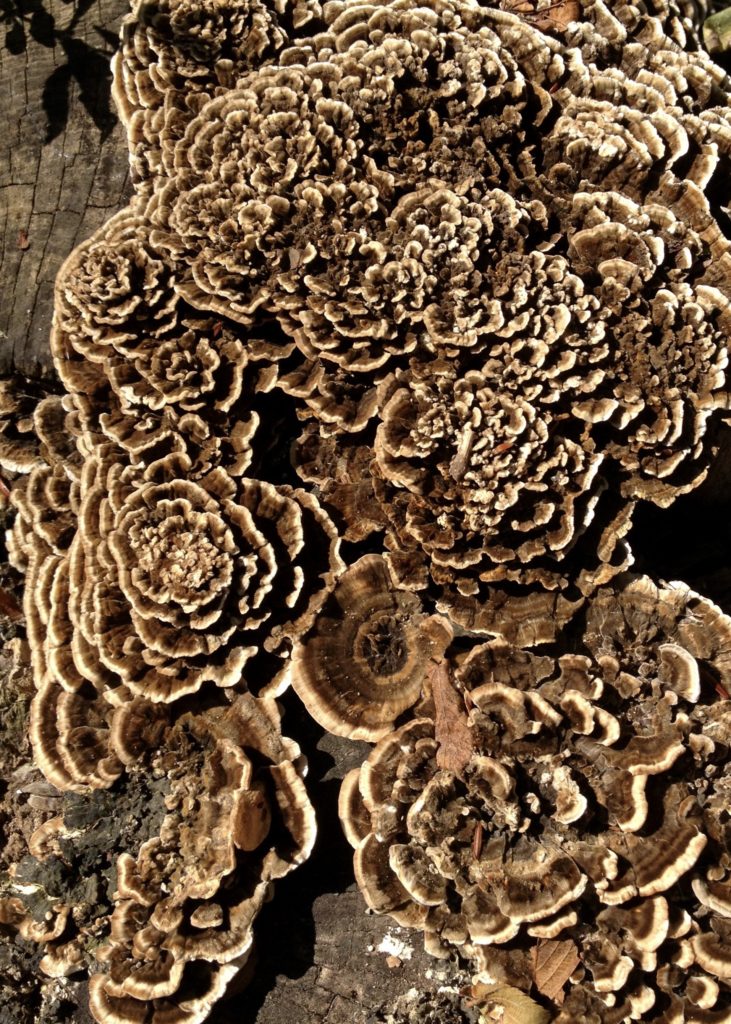

We are all born with this capacity for present-centredness. And if we’re lucky, we have time in childhood to spend time in this present state, especially in the natural world. Some children do not have these same opportunities and may not even have access to forests or anything considered wild. I consider myself lucky to have grown up in a time when kids roamed outdoors for hours at a time. We lived on a cul-de-sac with a school across the street and a forest at the end. The picture above is from that forest, although the bridge was made of wood back then. I spent many hours building forts in “the woods” and playing communal and solitary games in the field at the school. I also ice-skated several times a week at the local rink and the practice of doing figure eights over and over again was a centering practice for me, although I didn’t realize it at the time.

Even if you did have time in nature as a child, this quality of present-centredness often atrophies as we grow older and take on more responsibilities. We become, quite naturally, future and goal oriented. Therefore, we need a practice – whether it’s photography or hiking or meditation – to have access to the natural world and to maintain this quality of present-centred experience throughout our lives. I lost some of this present-centredness as I grew older and moved through school and into the working world. Having kids of my own helped me regain some, but it was the practice of photography, and especially the contemplative kind, where I began to feel that deep connection once again. And that’s made all the difference.

Discovering a World of Enchantment (middle childhood)

”The nature-oriented task of the next stage, middle childhood (approximately age four until puberty) is to learn the enchantment of the natural world through intimate contact with the wild, other-than-human world — a world found in the backyard, the nearby woods and thickets, the ditch or creek, the prairie, the mountains, or the beach, and the mind-boggling diversity of plants and animals living in each (unruined) place. The night sky, too, is an essential realm of enchantment — the Moon, local planets, and the countless stars and galaxies. In this we discover our membership in this greater, natural world that is the other half of her birthright beyond family, school, and market.” ~ Bill Plotkin

As a kid, I don’t remember feeling enchantment as I roamed the woods. At least I didn’t put that kind of language to it. Maybe the exposure just became a part of me and I didn’t have to attach words or meaning to the experience. It wasn’t something my parents ever talked about either. I just knew that I loved being outdoors and especially in the woods. Years ago, I volunteered at a Center in a city park where kids from inner city schools would come to the woods. Many of these kids had never been in a forest before and were afraid of it. After some encouragement, we watched them relax and saw a form of enchantment set in.

How many adults today never set foot in a forest, or very rarely?

I was also exposed as a child to the wonder of growing food. My great-grandparents grew acres of grapes and sold them for juice. Picking those grapes and popping them into my mouth was a sensual experience that stays with me to this day. The skins were smooth and strong and when my teeth bit through that skin, the sweet juice exploded in my mouth. My grandfather had a large vegetable garden and I spent many hours husking corn, picking beans, and shelling peas for our Sunday family dinners. I knew the goodness of fresh fruits and vegetables in season. Sadly, there are many that do not know the pleasure of good fresh food.

Today, I make it a priority to have frequent time around trees and near water. I pay close attention to seasonal changes in the landscape and what’s growing and blooming. Getting to know the geological and natural history of the place where I live is something I’m focusing on, as well as becoming aware of the current challenges this area is facing. A small garden provides me with some vegetables and herbs in the summertime. I want this place to be my true home, where everything plays an essential part, including me. I want to feel a sense of responsibility towards keeping my place (and me) healthy.

Next week, I’ll share a story about another eco-awakening that happened to me in middle adulthood. In the meantime, I hope you’ll think about your own childhood – what you had and what you might have missed. Did you have a formative experience in nature as a child? How do you keep that alive now?

* Here’s a post I wrote about Thomas Berry, called We Are the Earth.