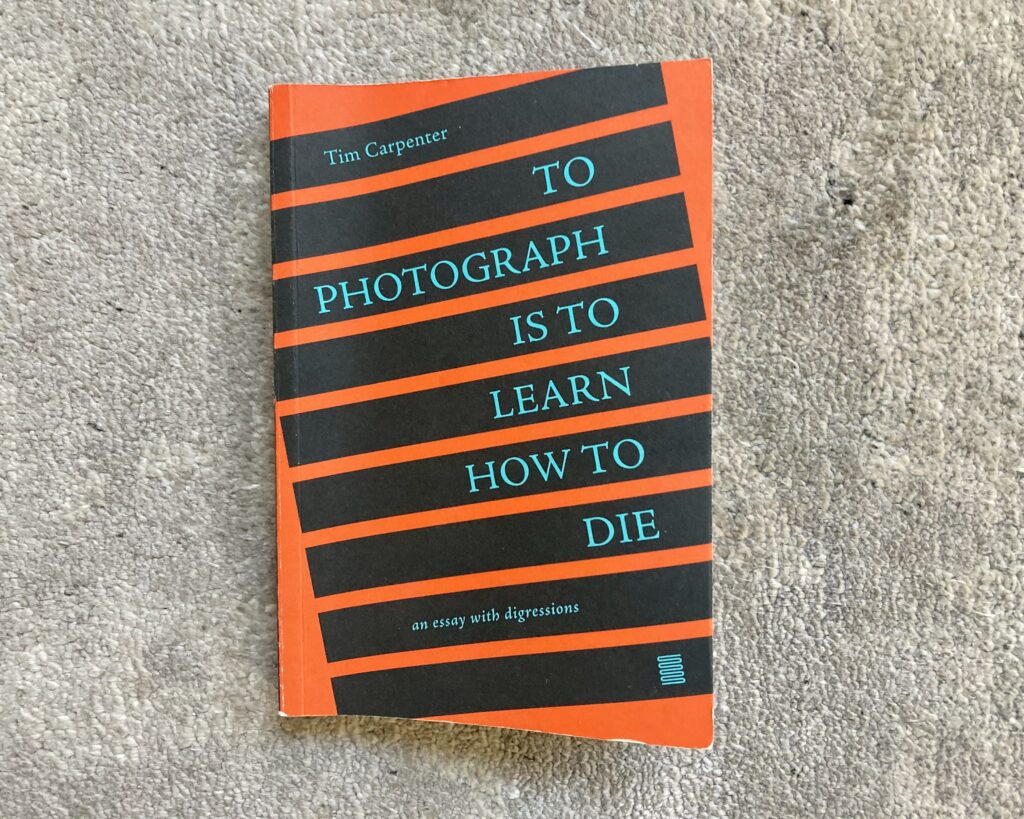

Tim Carpenter’s book, To Photograph is to Learn How to Die, certainly has a provocative title, yet it has been a surprise bestseller and has already gone through several printings. Although not an easy read, it’s by far one of my favorite books of the year. I read it through once on my own and then slowly (10-20 pages at a time) with a friend. We each submitted questions for discussion, which you can find through the button at the end of this post. .

Premise

Carpenter is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Illinois, who clearly loves his medium. He begins, and repeats throughout, the premise that there is an ongoing struggle or tension (and sometimes correspondence) between “what is” (the givenness of the world) and “what is not” (the sense we make of it). These are fundamental limitations that we always have to live with. For him, the camera is the most useful machine he has ever encountered for navigating this tension between himself and the world.

As humans, we are compelled to try to make sense of the world and some even to create aesthetic objects using our imagination. These aesthetic objects are attempts to breach the separation and affirm life. In this book, Carpenter focuses on poems and photographs. In each of the four sections, Carpenter builds his case, backed by the writings of philosophers, poets, and photographers. It’s unusually laid out in that the nuts and bolts of the book are presented in black type, quotes are in red, and digressions that add clarity and context are in blue.

Overall, this book is a philosophical treatise on contemplative photography and how the camera teaches us to be in the moment and accept life on its own terms. This reminds me of one of my favorite quotes by Dorothea Lange, “The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” Below are my thoughts on the major themes presented in the book.

Self and Separation

Carpenter made me think about the “self,” how it’s created and what it brings to the creation of an aesthetic object. For him, “self” is not “soul,” which is considered eternal. Rather, it’s internal, created over time from our experiences and choices made in life. The self is always changing and it informs our ethics, our behaviour, our posture or perspective or approach to facing the world. The self is not separate, yet our human consciousness perceives a separation. This perception creates a feeling of disconnection or something missing, which leads to expectations and longings. For Carpenter, this is the source of the tension between what is (the world) and what is not (the self).

The self experiences the world through the body, via sensation. Thoughts then follow, which are influenced by ephemeral things like memories, desires, hopes and plans, fears and anticipation. Based on these things, we make our choices in the present. The self changes when new experiences present themselves or when we practice scrutinizing our preconceived ideas and learn from new information. In other words, we can see differently and make different choices.

Impermanence and Humility

Carpenter delves into the fact that impermanence is fundamental to human existence. One way to accept impermanence is through the quality of humility, seeing ourselves as naturally limited and always being open to new insights. Carpenter believes that the camera can be a tool for embracing the impermanence of life. I do too and I created a whole course on celebrating impermanence (free PDF). The reason that photography works so well for this is because it’s the most limited in terms of time and the actual. For the photographer, the picture can only be made now, which perfectly mirrors the human experience. The photographer is constantly reminded to accept limitations and constraints, to accept what can’t be controlled, and to learn from the world.

Each moment becomes an act of creation, where we have to make choices. The fact that we can make a choice, no matter the situation, is the source of true freedom. While never truly free from the feeling of separation, we still have the freedom to manage and shape our responses. In Carpenter’s words, we can just stop complaining and learn to get along in the world, to deal with it as it is and respond in the most effective way to make the world a better place.

Creation and Decreation

Carpenter then goes on to describe the making of an aesthetic object. We create because we long for a direct connection between self and not-self, even though it will rarely or may never happen. Not everyone feels compelled to create aesthetic objects, however, so what is it about those who do? This question reminded me of one of my favorite quotes, one that explains my relationship to photography, “All of my creation is an effort to weave a web of connection with the world: I am always weaving it because it was once broken.” ― Anaïs Nin, The Diary of Anaïs Nin, Vol. 3: 1939-1944

Creation begins with desire or absence or longing; something that arises internally. When this desire meets the world (subject matter, what is given), it creates possibilities, which are manifested through form – the meaning overlaid by the creator through a set of relationships. There is the initial perception of the moment, followed by the shaping of that perception into an aesthetic object. Before this shaping can happen, though, there first must be a practice Carpenter calls “decreation,” culling what’s not essential and eliminating the projections of self onto the creation. As humans, we’re very good at projecting our received ideas and ideologies onto the world and our creations.

The first step of decreation is forgetting the past. This may sound strange, yet Carpenter tells a fascinating fact about memory; that we’ve already forgotten almost every bit of our direct experience. This erasure of specifics is a necessary part of being human and is what shapes us as individuals. We need to eliminate excess and decide what to remember in order to grow. This letting go of memory is what helps our imagination take flight, opening us to new possibilities in the present. Shaping meaning or making an object is an active form of forgetting.

The second part of decreation is the deliberate diminishment or elimination of projections and a deference to the real (what is). This can also be called unselfing, where we scrutinize our preconceived ideas. Although a photograph will always be an abstraction (a part of reality, not the whole), it comes closer to reality than other mediums, and so we can’t deny what is right in front of us. The photographer works with the premise that one cannot shape the world to one’s desire. In other words, they work with what they’ve got; a good rule for life.Through our choices in framing and perspective, we form meaning and get to know ourselves and the world in the process.

However, it’s not possible to eliminate our projections 100%; we’ll always bring some of our ideas to the work. Still, we can occasionally get glimpses of wholeness, moments of transcendence or epiphanies. Decreation is just a method, an active skill or attitude with the goal of letting go of our established attitudes and focusing on the present; seeing new possibilities. The camera becomes an extension of mind, where we think with and through it. Photographic seeing becomes an intentional way of discovering the relationships between self and not-self.

Using Imagination to Affirm Life

Imagination is central to the creative process. It springs from our expectations and longings, allowing us to ponder what is not; to consider possibilities beyond the immediate environment. Samuel Taylor Coleridge divided the imagination into two parts – primary and secondary. The primary is basically our daily response to life, the moment to moment making sense of things, often unconscious. For example, there is a curb so you lift your foot. The secondary is when you extract yourself from the day to day to observe what’s happening, and create something meaningful from it.

Carpenter believes that to make our way in the world, we need to accept our limitations and use our imaginations to create aesthetic objects that affirm life. The best art, whether a photograph or a poem or a painting, affirms life by expressing its beauty and significance. Personal connection to the subject matter falls away, and becomes irrelevant to the final product. The aesthetic object transcends the self and the not self. It is useful if it is beneficial to human flourishing, if it helps us to understand ourselves, or is able to communicate something of significance to others.

In summary, to photograph is … to learn how to reconcile our limitations, to be of use, to learn how to die and therefore, learn how to live.

I found this book to be very resonant with my own experience of photography. How about you? Did you read this book? Please add your comments to the discussion.